Diagnosis and Classification of Asthma in Adults and Children Over 5 Years of Age

Recurrent episodes of coughing or wheezing are almost always due to asthma in both children and adults. Cough can be the sole symptom. Performing a complete medical history and physical examination can assist in diagnosing asthma.

Consider a diagnosis of asthma and performing spirometry if any of these indicators is present.* These indicators are not diagnostic by themselves, but the presence of multiple key indicators increases the probability of a diagnosis of asthma. Spirometry is needed to establish a diagnosis of asthma.

Consider a diagnosis of asthma and performing spirometry if any of these indicators is present.* These indicators are not diagnostic by themselves, but the presence of multiple key indicators increases the probability of a diagnosis of asthma. Spirometry is needed to establish a diagnosis of asthma.

Wheezing–high-pitched whistling sounds when breathing out–especially in children. (Lack of wheezing and a normal chest examination do not exclude asthma.)

History of any of the following:

- Cough, worse particularly at night

- Recurrent wheeze

- Recurrent difficulty in breathing

Symptoms occur or worsen in the presence of:

- Exercise

- Viral Infection

- Animals with fur or hair

- House-dust mites (in mattresses, pillows, upholstered furniture, carpets)

- Mold

- Smoke (tobacco, wood)

- Pollen

- Changes in weather

- Strong emotional expression (laughing or crying hard)

- Airborne chemicals or dusts

- Menstrual cycles

Symptoms occur or worsen at night, awakening the patient.

*Eczema, hay fever, or a family history of asthma or atopic diseases are often associated with asthma, but they are not key indicators.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

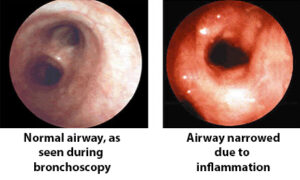

The upper respiratory tract, chest, and skin are the focus of the physical examination for asthma. Physical findings that increase the probability of asthma are listed below. The absence of these findings does not rule out asthma, because the disease is by definition variable, and signs of airflow obstruction are often absent between attacks.

- Hyperexpansion of the thorax, especially in children; use of accessory muscles; appearance of hunched shoulders; and chest deformity.

- Sounds of wheezing during normal breathing or a prolonged phase of forced exhalation(typical of airflow obstruction). Wheezing may only be heard during forced exhalation, but it is not a reliable indicator of airflow limitation.

- Increased nasal secretion, mucosal swelling, and/or nasal polyps.

- Atopic dermatitis/eczema or any other manifestation of an allergic skin condition.

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING (SPIROMETRY)

The Expert Panel recommends that spirometry measurements—FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 6 seconds (FEV6), FVC, FEV1/FVC—before and after the patient inhales a short-acting bronchodilator should be undertaken for patients in whom the diagnosis of asthma is being considered, including children ≥ 5 years of age. These measurements help to determine whether there is airflow obstruction, its severity, and whether it is reversible over the short term. Patients’ perception of airflow obstruction is highly variable, and spirometry sometimes reveals obstruction much more severe than would have been estimated from the history and physical examination.

ADDITIONAL TESTS FOR ADULTS AND CHILDREN

Additional tests may be needed when asthma is suspected but spirometry is normal, when coexisting for other reasons. These tests can aid diagnosis or confirm suspected contributors to asthma morbidity (e.g., allergens and irritants).

| Reasons for Additional Tests | The Tests |

|---|---|

Patient has symptoms but spirometry is normal or near normal | Assess diurnal variation of peak flow over 1 to 2 weeks Refer to a specialist for bronchoprovocation with methacholine, histamine, or exercise; negative test may help rule out asthma |

Suspect infection, large airway lesions, heart disease, or obstruction by foreign object | Chest X-ray |

Suspect coexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, restrictive defect, or central airway obstruction | Additional pulmonary function studies Diffusing capacity test |

Suspect other factors contribute to asthma (these are not diagnostic tests for asthma.) | Allergy tests – skin or in vitro Nasal examination Gastroesophogeal reflux assessment |

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ASTHMA IN ADULTS

- COPD (e.g., chronic bronchitis or emphysema)

- Congestive heart failure

- Pulmonary embolism

- Mechanical obstruction of the airways (benign and malignant tumors)

- Pulmonary infiltration with eosinophilia

- Cough secondary to drugs (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors)

- Vocal cord dysfunction

Once asthma has been correctly diagnosed, the next step in patient care is to classify the severity of the disease. Use the chart below to help you assign a severity level to your patient, based on the domains of impairment and risk.

ASSESSMENT OF IMPAIRMENT

Assessment of severity requires assessing the following components of current impairment:

Symptoms

- Nighttime awakenings

- Need for SABA for quick relief of symptoms

- Work/school days missed

- Ability to engage in normal daily activities or in desired activities

- Quality-of-life assessments

Lung function, measured by spirometry: FEV1, FVC (or FEV6), FEV1/FVC (or FEV6 in adults). Spirometry is the preferred method for measuring lung function to classify severity. Peak flow has not been found to be a reliable variable for classifying severity, but it may serve as a useful tool for monitoring trends in asthma control over time.

ASSESSMENT OF RISK

A closely related and second dimension of severity is the concept of risk of adverse events, including exacerbations and risk of death. Assessment of the risk of future adverse events requires careful medical history, observation, and clinician judgment. Documentation of warning signs and adverse events will be necessary when a patient is felt to be at increased risk.

- Assessing the risk of exacerbations is through questions regarding the use of medications, particularly oral corticosteroids, or urgent care visits. Low FEV1 is associated with increased risk for severe exacerbations.

- Assessment of the risk of progressive loss of lung function, or, for children, the risk of reduced lung growth (measured by prolonged failure to attain predicted lung function values for age) requires longitudinal assessment of lung function, preferably using spirometry.

- Assessment of the risk of side effects from medication(s) does not directly correspond to the varying levels of asthma control. For example, a patient might have well-controlled asthma with high doses of ICS and chronic oral corticosteroids but is likely to experience some adverse effects from this intense therapy. The risk of side effects can vary in intensity from none to very troublesome and worrisome.

The next step in caring for your patient with asthma is to develop a treatment plan that addresses their medication needs and avoidance strategies based on current level of severity.

Learn more about the stepwise approach recommended by the NIH for the management of asthma in adults and children over 12 years old.

Learn about Asthma Action Plans.

Learn when to refer patients to an asthma specialist.

Learn what makes a patient have an increased risk for death from asthma.

Adapted from the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Expert Panel Report 3, 2007.