Predicting Which Children Will Get Asthma

Health professionals and parents have long known that infants and small children will wheeze more than older children and adults, and that sometimes it leads to asthma. But it is often hard to diagnose asthma in such young patients, and until recently, hard to predict which child would develop persistent (life-long) asthma, and which would seem to "outgrow" it.

Wheezing is very uncommon during the first two months of life, but in the next few months, first-time wheezing increases, peaking between two and five months of age. Infants' airways (compared to older children and adults) are smaller around, have less smooth muscle and make more mucus, which can lead to more coughing, wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath, or rapid breathing. Most wheezing during the first three years of life is related to viral respiratory infections, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Respiratory viruses and symptoms of early asthma may be hard to tell apart, making diagnosis and treatment tricky. But doctors and parents now have tools to help them predict with reasonable accuracy if the child will develop asthma.

High-risk children (under age three) who have had four or more wheezing episodes in the past year that lasted more than one day, and affected sleep, are much more likely to have persistent (i.e., life-long) asthma after the age of five, if they have either of the following:

One major criteria:

- Parent with asthma

- Physician diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (often called eczema)

- Evidence of sensitization to allergens in the air (i.e., positive skin tests or blood tests to allergens such as trees, grasses, weeds, molds, or dust mites)

OR

Two minor criteria:

- Evidence of food allergies

- 4 percent or more blood eosinophilia (Increased numbers of white blood cells called eosinophils are made by the body to fight off allergic disease. They can collect in tissues and cause damage to the airways of the lung.)

- Wheezing apart from colds

The API was developed after following almost a thousand children through 13 years of age. Seventy-six (76%) of children diagnosed with asthma after six years of age (considered persistent or life-long asthma) had a positive asthma predictive index before three years of age. Ninety-seven (97%) of children who did not have asthma after six years of age had a negative asthma predictive index before 3 years of age.

This data lends a strong argument for use of the API routinely in young children. With the insight the index provides, doctors and parents can watch more closely for symptoms of asthma as the child grows, and if needed, start the right medications earlier. Earlier and better treatment can help keep children active and healthy, and their asthma in good control.

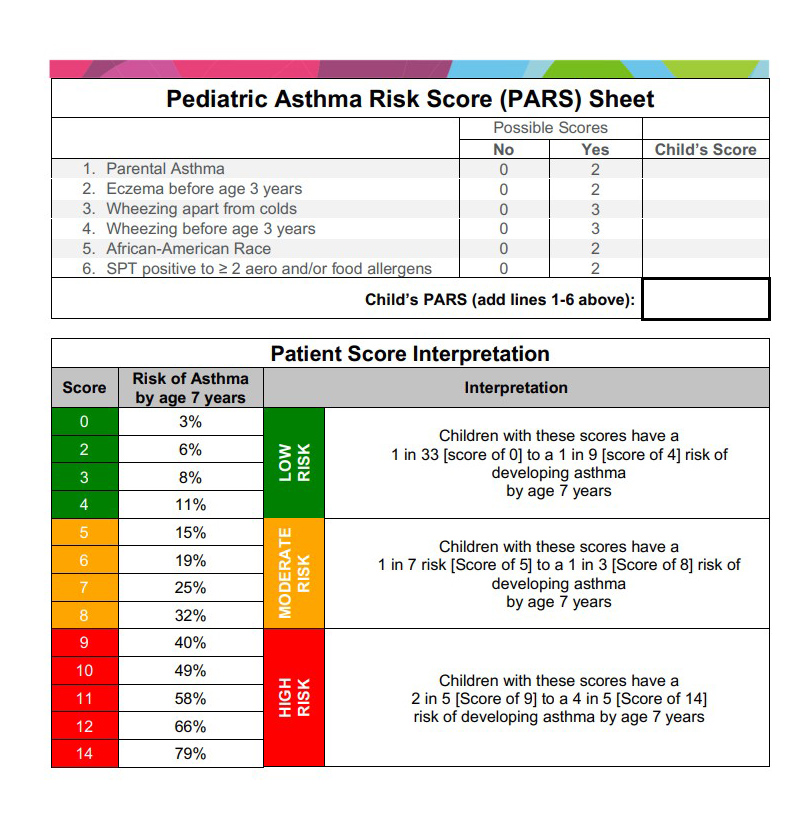

PARS addresses the need for an improved screening tool that identify children at risk of developing asthma using a continuous outcome scale and personalized demographic and biomarker risk factors. It was designed to be easily used within the general pediatric setting without the need for multiple blood tests so that the risk evaluation could be completed in the same, initial visit in which the family or provider’s concern arises.